Females and felines. They go way back.

But why that particular popular cultural association? Perhaps partly because both women and cats are often seen as graceful, beautiful, and somewhat mysterious. Both were traditionally domestic.

“Think of a stylization of a cat,” wrote Kayla Green-Wall. “Now, think of a stylization of a pin-up model. Sleek and slinky, with a heart-shaped face, big eyes, and glossy hair, right? Now, think of the femme fatale stereotype: deceptively languid but probably dangerous, right?”

Whatever the reasons, this association has been relentlessly underlined in superhero stories — not just DC’s Catwoman, but Harvey’s Black Cat, Marvel’s Black Cat, Fiction House’s Tiger Girl, Gold Key’s Tiger Girl, Marvel’s the Cat and Hellcat and Tigra, DC’s Tigress, Republic Studios’ Panther Girl, and so on and so on.

And Archie Comics had Cat Girl.

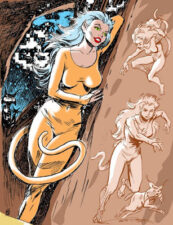

Introduced in The Adventures of the Fly 9 (Nov. 1960), Lydia Fellin was “…the Sphinx, the original model for the countless ancient statues.” The superhuman feline immortal clashed with the superhero when she freed big cats from their imprisonment in a zoo. She kept returning, eventually making a dozen appearances in Archie Comics.

Super-strong and armed with claws, Cat Girl was indestructible and could become invisible, fly, teleport, telepathically communicate with cats, and gaze into the future.

After several encounters with the Fly, she concentrated her attention on the Jaguar, Archie Comics’ other superhero of the early 1960s, and promptly fell in love with him.

Seemingly inadvertently, the Jaguar turned out to be quite the lady killer. Superwomen, alien women, and ordinary women were forever becoming infatuated with him. The Adventures of the Jaguar threatened to become “Catfight Comics.”

“(T)he valorous Jaguar has the benefit of being ‘the world’s most attractive bachelor,’ as the text repeatedly tells us,” wrote Jon Morris in his book The Legion of Regrettable Supervillains. “What’s Cat Girl to do? It’s no wonder that while trying to conquer the world, she can’t help feeling giddy in the presence of such a superheroic hunk.”

“Any cunning I now possess I shall use to win your heart!” she vowed. “I’m still madly in love with you, Jaguar!”

To that end, she rescued him from aliens, wooed him with love potions, and helped him out by breaking up a ring of cat burglars (who wore cat masks, naturally).

Cat Girl also joined the all-female “Jaguar Rescue Team.”

“In sponsoring this assemblage, the Jaguar may have created every superguy’s worst nightmare: a team made up entirely of ex-girlfriends,” Morris quipped.

Cat Girl would eventually lose most of her supernatural powers by being exposed to radiation from a nuclear testing site, retaining only her telepathic control over cats. Undaunted, she continued her romantic pursuit of the Jaguar as a jet-set socialite.

Archie’s Cat Girl may well have been a wink at DC’s Catwoman, the popular 1940s villain who nevertheless hadn’t appeared in six years (since The Jungle Cat-Queen in Detective Comics 211, Sept. 1954). No successful concept is ever abandoned in superhero comics. It’s always recycled — if not by the original publisher, then by another.

In fact, one Cat Girl wasn’t enough for Archie Comics. They had to have two. The second was a sultry character in a black leotard meant to complement Archie’s movie monster parodies and a nod at the two RKO Cat People films made in the 1940s.