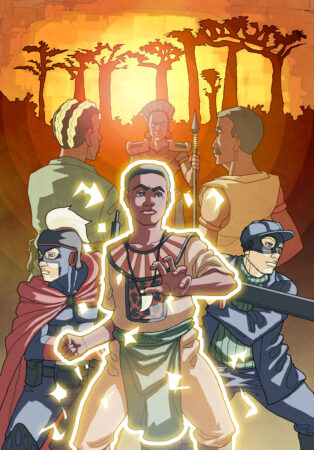

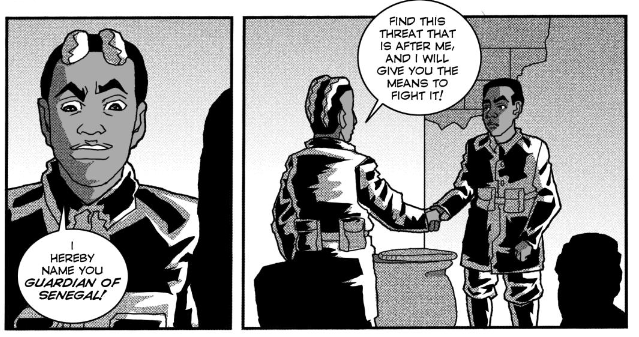

The Guardian of Senegal first appeared in Partisans #2 as written by Jean-Marc Lofficier. The newest graphic novel from Hexagon, The Guardian of Senegal, is an exciting look at the character’s origin, featuring the title character as well as two different Guardians of the Republic, historical figures from Senegal and France, with opposition from the Twilight People and race of Jinn. A story of history, family, and becoming a hero.

I had the opportunity to interview the creator of the Guardian of Senegal and publisher of Hexagon, Jean-Marc Lofficier (from France) as well as the creative team behind just released Guardian of Senegal one shot, Mouhamadou and Narotam (both from Senegal) and I invited noted poet and comic fan from Capetown, South Africa, Oliver Abrahams to interview the trio with me (I’m from Cleveland, Ohio) for this multinational interview.

Joeseph Simon: Jean-Marc, what prompted you to add a hero from Senegal to the Partisan’s roster? Did you, at the time, have larger plans for the hero?

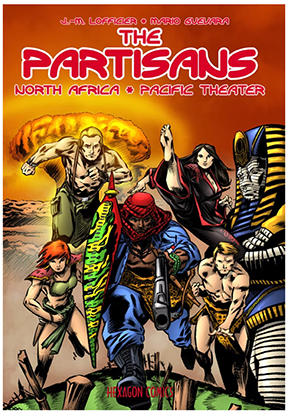

Jean-Marc Lofficier: After the initial team of Partisans, who fought in Europe, I thought I should add a team who fought in the Pacific. Then my friend writer Romain d’Huissier suggested a third team, who fought in North Africa. I wanted to include in it an African hero from the French then-colonies, and that’s how the idea of a Guardian of Senegal was born. At that point, I knew right away that when the opportunity arose, we would have a special issue devoted to his origins and back story, which is why I left his background purposefully mysterious in The Partisans.

JS: Jean-Marc, how did you find yourself publishing a superhero comic featuring a political cartoonist with Narotam and a fiction writer with Mouhamadou, both from Senegal?

Jean-Marc: Mouhamadou, I already knew because we had published a sci-fi vampire novel of his (Sapiens Vampiris) in our French book imprint, Riviere Blanche. I really liked the book, and I thought he had all the obvious qualities to be put in charge of creating an origin for our hero. Finding an artist was much more difficult. I asked for recommendations, I sent an email to a local art school (no reply), a local comic club (no reply)… In short, it took me a year or so to finally connect with Narotam!

JS: To Mouhamadou and Narotam, what did each of you think of Kanta’s first appearance in Partisans?

Mouhamadou: I was really happy to see a Senegalese character in the comic book, as it resonates with the historical participation of Senegalese soldiers during World War I and their assistance to France. Kanta’s character was also very mysterious, which naturally raised a lot of questions, such as where he met Satanik, the origins of his powers, etc. I really appreciated the opportunity Jean-Marc gave me to write that story.

NAROTAM : Kanta is a wonderful character who attaches great importance to his origins. I had great pleasure in illustrating his adventures, and I am very proud of it because it allows me to share certain aspects of my culture with readers.

JS: History plays an important part in your story where you go back to tell the Guardian of Senegal’s origin starting in 1914 (and continuing through 1938). What about this period of time is important to each of you?

Mouhamadou: This period was crucial for Senegal and other West African countries in gaining their independence. First, there was the demystification of the ‘white man,’ as our soldiers witnessed them fall on the battlefield. Additionally, many black students, like Kanta, went to France to study and formed small intellectual groups that would later fight for their countries’ independence. Without these developments, colonization might have lasted longer, and the opportunity for us three to collaborate on this comic book may not have existed.

NAROTAM : These two dates remind me of the colonial period of many African countries, including my country Senegal. With the history of the riflemen who fought for the French army during the world wars.

JS: Mouhamadou, the young Prince Sidya Leon Diop (and his mother) hold significant historical importance in Senegal. What other historical figures did you incorporate and why?

Mouhamadou: Ndatte Yallah (Sidya’s mother) and the women of Nder (a village in her kingdom) are great symbols of courage and resilience in our culture. Sidya was taken from his mother at a young age, raised and educated in France, and nearly brainwashed. However, upon returning to Senegal and reconnecting with his roots, he defended his people and reclaimed his position as the Prince of Walo. This story resonated deeply with what I wanted to express in our narrative. Additionally, Kanta’s grandfather is inspired by the Senegalese scholar Cheikh Omar Foutiyou Tall. He was a wise man who fought against colonizers with weapon, but also emphasized the importance of education for his people, considering it the greatest weapon. He performed many miracles during his life, with some believing he never died. His story also blends well with the world of the guardians.

JS: Speaking of history, Hexagon has an incredible history going back further than Marvel comics!

Both of you, not only contributed to that history, you were able to include a few of its great characters like Guardian of the Republic to the Twilight People and even Scarlet Lips’ gift in your storyline. How was it writing these into your story? Or being the artist to depict them?

Jean-Marc: I confess to being responsible for adding these few connections to the rest of the Hexagon Universe to the story during the editing stage. The Jinn Shaitanik had already been featured in The Partisans #2 so Mouhamadou had incorporated him and his kind in the story at my request. Mentioning Scarlet Lips en passant was just a cherry on top. More important, however, were the role of the two previous Guardians in the story. They, too, were part of the “brief” I had handed to Mouhamadou, more specifically, that during World War I, the French Guardian would be killed and replaced (temporarily) by our hero’s father or grandfather – the family relationship wasn’t specified in that “brief”; that took form in Mouhamadou’s story. As for the WWII Guardian (the one from the Partisans), he was also mentioned in the “brief” as someone Kanta would meet or would influence him, etc. Again, nothing was firmly set. It was up to Mouhamadou to integrate him in the plot, and he did it very well, even adding a sidekick, which I named (La Mécanique).

From a practical standpoint, I couldn’t expect Mouhamadou to catch up with 20 years of Hexagon history, so it was my role as editor to make sure the story would integrate smoothly within our universe, and even, as it turned out, add to it.

NAROTAM : For me, it’s a new universe that I’m discovering, because it’s my first collaboration with Hexagon comics. As a result, I was forced to adapt to new character models that already existed in the universe Hexagon. For this, I based myself on the artworks of other artists who have already worked in the universe, so as not to go off topic…And Jean-Marc helped me a lot, by providing me with the illustrations and the references of the main characters.

JS: Mouhamadou, how different was writing Guardian of Senegal to writing your critically acclaimed novel Sapiens Vampiris?

Mouhamadou: From a creation standpoint, I found writing ‘Guardian of Senegal’ easier. It’s a magical story, and Jean-Marc gave me a brief while allowing me the freedom to shape the new characters as I saw fit. On the other hand, ‘Sapiens Vampiris’ is a sci-fi novel, so there’s a need to ensure that everything can be scientifically backed. The most challenging aspect of writing a comic was mastering the technique, which was quite new to me. It involves decomposing the story in your head and laying it out panel by panel with specific imagery to convey each scene. Describing scenes for the artist was also a challenge, but fortunately, Narotam is not only incredibly talented but also deeply understands the story. From the first three pages he shared with me, I knew our collaboration would be very smooth

Oliver Abrahams: What difficulties did you have getting Sampiens Vampiris published due to being from Senegal?

Mouhamadou: It wasn’t easy to get ‘Sapiens Vampiris’ published, especially being from Senegal where we have few publishers, and most don’t sell internationally. Many of our renowned writers, like Fatou Diome or Mbougar, live or have lived in France or Europe. I sent over 50 emails to publishers in France, receiving either negative replies or no response at all. Interestingly, I met Jean-Marc while trying to publish the second trilogy I am working on. He liked the synopsis but couldn’t publish it as it was fantasy, not sci-fi, which is his publishing company’s focus. However, he expressed interest in publishing a sci-fi novel based on African history and mythology. And I was like, ‘I’ve got the perfect book for you.’

JS: Narotam, how different was this from creating political cartoons?

NAROTAM : These are two very different worlds. The caricature is inspired by news items related to current events. The illustrations that I produce for any newspaper are done from day to day according to needs. On the other hand, working on a comic requires the management of an artistic project which can take months or even years. It is a work that requires a lot more research and illustrations. You must therefore be very patient, start with the first page, then evolve little by little until the last.

JS: To both, what comics inspired your story or art for Guardian of Senegal?

Mouhamadou: Well, the foundational inspirations for ‘Guardian of Senegal’ were definitely the Guardians and the Partisans series, as they lay the groundwork and context for our story. In terms of character development, especially for Kanta, I drew significant inspiration from Spider-Man. Specifically, I was influenced by the classic Spider-Man comics, where Peter Parker is portrayed as a young, dynamic character grappling with newfound powers and responsibilities. His journey from a naive teenager to a more mature hero, balancing personal challenges with his superhero duties, resonated with me. This evolution of character, particularly the way Spider-Man navigates the complexities of youth and power while maintaining his core values, helped shape my approach to developing Kanta. The idea of a young, powerful, yet somewhat naive hero, learning to harness his abilities for the greater good and growing through his experiences, was something that I found compelling and relevant for Kanta’s character arc in ‘Guardian of Senegal..

NAROTAM : There’s not really a comic strip that inspired me in particular. When I work, I draw inspiration from almost everything in general… But especially from photos and written references.

Oliver: Are either of you inspired by African folk tales?

Mouhamadou: Absolutely, African folk tales, especially those from my Lebou heritage on my mother’s side, have always been a source of inspiration for me. The Lebou people have a rich tradition of stories involving interactions with Jinn, encompassing aspects of worship, conflict, and coexistence. These tales were a significant part of my childhood, narrated by my mother, sisters, and aunts. They often revolved around ‘Serignes’ and ‘Saltigues,’ humans endowed with magical powers used to combat or interact with these Jinn.

This rich tapestry of folklore has invariably influenced my artistic creations, whether it’s in the form of a novel or a comic book. The themes of magic, the supernatural, and the complex relationship between humans and mythical beings are elements that I find myself returning to frequently. In these stories, there’s a profound sense of mysticism and a deep connection to the spiritual world, which adds layers o f depth and meaning to the narratives. This connection to African folklore not only enriches the cultural context of my work but also allows me to explore universal themes through a uniquely African lens.

NAROTAM : Yes, it happens to me often, but it also depends on the projects I’m working on.

JS: Mouhamadou, Kanta, the Guardian of Senegal, knows Karamets. In the storyline, Kanta says Karamets is magic taught in his village. The word Karamet has another meaning as well. Are you, in part, referencing supernatural wonders performed by Muslim Saints?

Mouhamadou: Yes, the concept of Karamets in our story does reference the supernatural wonders often associated with Muslim Saints. However, it’s also true that in some villages in Senegal, children as young as eight or ten can perform these types of magic. It’s not exclusively a power of the Saints. In fact, most Saints, like Cheikh Omar Foutiyou, are reluctant to use it unless absolutely necessary. Karamets is not just a power; it’s an art form that anyone can learn, but it’s also dangerous, as it exposes one to the invisible world.

These stories are a part of the culture I grew up in. I wanted to convey that even though Karamets might be considered ‘white’ or ‘good’ magic, it can still be used for harmful purposes, as we discover towards the end of the book. This dual nature of Karamets is why many Saints and scholars choose not to teach or delve into it.

Oliver Abrahams: Aside from invisibility, what other powers does Kanta have with Karamets?

Jean-Marc: I might add here that Kanta also owns various magical talismans. I think I identified one as coming from Buluku, an ancient God from the Fon or Yoruba people, if my memory serves.

Mouhamadou: Additionally, the powers of Karamets are limitless but cannot be used just anytime or anywhere. They involve a pact between nature, the magician, and the ancestors. As depicted in the book, Kanta uses elements like wind or sand. As long as his ancestors support him, he can draw magic from these elements to achieve almost anything. He potentially could fly, dodge bullets, or move with super speed. However, using these powers independently, such as when he becomes invisible without an elemental aid, can be exhausting.

Karamets can also be augmented by Jinn magic, which would draw from the Jinn’s energy. But since Jinn are supernatural creatures, they have much greater endurance than humans.

JS: Speaking of the supernatural, Kanta finds danger in fighting against the Jinn. Who are they?

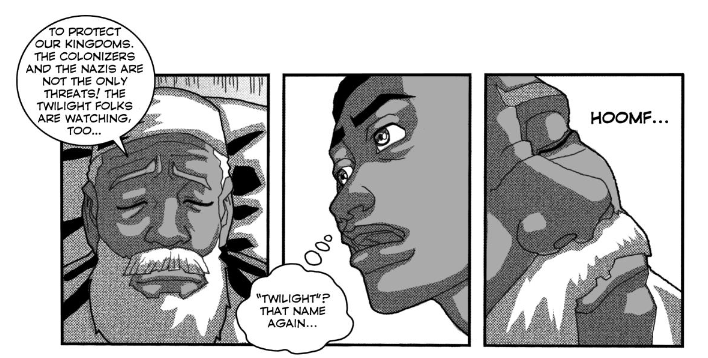

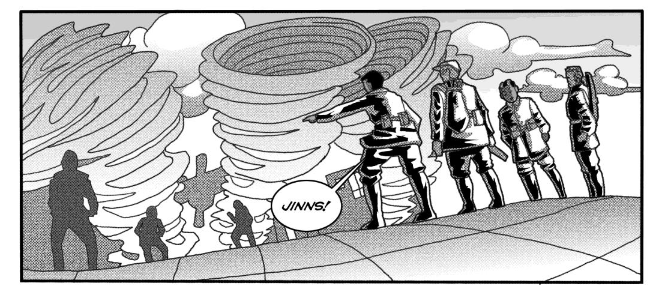

Jean-Marc: In the Hexagon Universe, the vampires, werewolves, etc., are not purely supernatural or magical creatures, but part of a race of beings who came from another universe and found refuge on Earth long ago. They’re called the Peuple du Crépuscule, or Twilight People. So while the jinns are exactly like described in the legends and folk tales of Africa and the Middle East, they are in fact part of the Twilight People, and, as hinted, somewhat in competition with the vampires.

Oliver: how long have the Jinn been a problem for Kanta’s people?

Mouhamadou: The Jinn have been a challenge for Kanta’s people since their arrival on Earth. Due to their knowledge of the mystic arts, the people of West Africa were difficult to conquer. This is why the Saltigué have always served a dual role: as protectors of the people and as masters of magic.

JS: To everyone: Where history is an important part of Kanta’s story, family is equally important. Kanta is further empowered by his family’s love, their knowledge, and in other ways as well.

Mouhamadou: Family holds a central place in my life, especially as a member of the Lebou community. Our culture deeply values familial bonds, to the extent that our language predominantly uses ‘we’ instead of ‘I’, emphasizing the collective over the individual. This reflects our belief in the strength and unity of the family unit. Our family names carry significant weight, as they convey the glory of our past and the exploits of our ancestors.

Expressing this deep-seated value of family in a comic was both a challenge and an honor. In ‘Guardian of Senegal’, Kanta’s empowerment through his family’s love and knowledge is a reflection of my own experiences and cultural values. The comic medium allowed me to visually and narratively showcase the importance of family and history, intertwining them with the story’s central themes. It was important for me to depict how family and history are not just background elements, but active, empowering forces in Kanta’s journey. Their influence is a driving force in the narrative, mirroring the profound impact they have in our lives.

JS: I’m curious about the value history and family are to each of you and how it was to express such valued subjects in a comic?

Mouhamadou: I am very enthusiastic about the prospect of writing another story with Kanta. There’s so much more to his character and journey that remains unexplored. At the end of the current story, Senegal is still on the path to independence, and Kanta, alongside Prince Sidya, has much to contend with. As the new Saltigué, his duty extends to protecting all the West African kingdoms from the Twilight People. There are also unresolved questions about his future: Will he return to France? What will happen with his friend Eric? Will Sedar learn Karamets? There are numerous plot lines to explore, and family will always be at the heart of these stories. As I mentioned earlier, Karamets work with the support of ancestors, symbolizing the theme that they help primarily to protect their own kin.

NAROTAM : Family is very important to me, and it is also important in most African societies. It is a basic structure that conveys a whole set of cultural and traditional values necessary for community life. In Senegal, each family has a story that has followed them since pre-colonial times. The guarantors and protectors of each family’s history are called griots. They are both scribes, and good orators for my country.

Oliver: You can see the importance of family comes through in the story, especially when his Grandfather dies. It reminds me of movies like Blue Beetle and Black Panther where the family plays just as much an important part of the story as the main character. Remembering your roots, it helps the characters stay grounded.

If you get to write more of Kanta’s story, will we discover more about his family?

Jean-Marc: There were a lot of practical problems working with Senegal. You wouldn’t believe how hard it was to send money there to pay Mouhamadou and Narotam. That said, if this issue does well, I would like to eventually commission another story, taking place around 1940, explaining how Kanta met young Tanka from the neighboring (but fictional) country of Karunda and what role he played in teaching him to become a hero. The rest will be up to Mouhamadou.

NAROTAM : Yes certainly, and that would make me very happy, but it will be more up to the screenwriter…

JS: In Senegal, how are comics thought of? Are there comic stores or independent comics in Senegal? What foreign comics get distributed there and where are they sold?

NAROTAM : Senegalese society is generally not yet very steeped in the culture of comics. However, the media does exist, and there are more and more young people who are interested in it. It is possible to find comics or manga in certain bookstores in large cities like Dakar.

The Guardian of Senegal is on sale now and can be found at

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Guardian-Senegal-Mouhamadou-Moustapha-Sy/dp/1649322631

Directly from Hexagon: https://www.hexagoncomics.com

Thank you to

Jean-Marc Lofficier is a French author of books about films and television programs, as well as numerous comics and translations of a number of animation screenplays.

Writer Mouhamadou Moustapha Sy is a young Senegalese engineer who has been passionate about storytelling since childhood. He first wrote fanfiction before being published professionally. His first novel, Sapiens Vampiris by Riviere Blanche, was published in France in 2021 to critical acclaim.

Artist Narotam works as a cartoonist for a satirical Senegalese newspaper, Le Politicien, one of the first independent newspapers launched in Senegal after its independence. His works combine irreverent humor, political caricature, and journalism, often relying on confidential sources. He is now trying to expand his horizons by drawing comics in the Franco-Belgian style

Guest /co-interviewer, Oliver Abrahams is a published poet. His poetry collection, Planet Earth speaks of African history and gives hope for a better humanity. Oliver is a long time comic book fan and aspiring musician from Capetown, South Africa.